Conversation with Rosa Joly

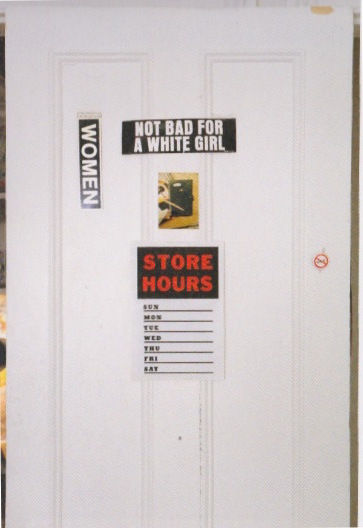

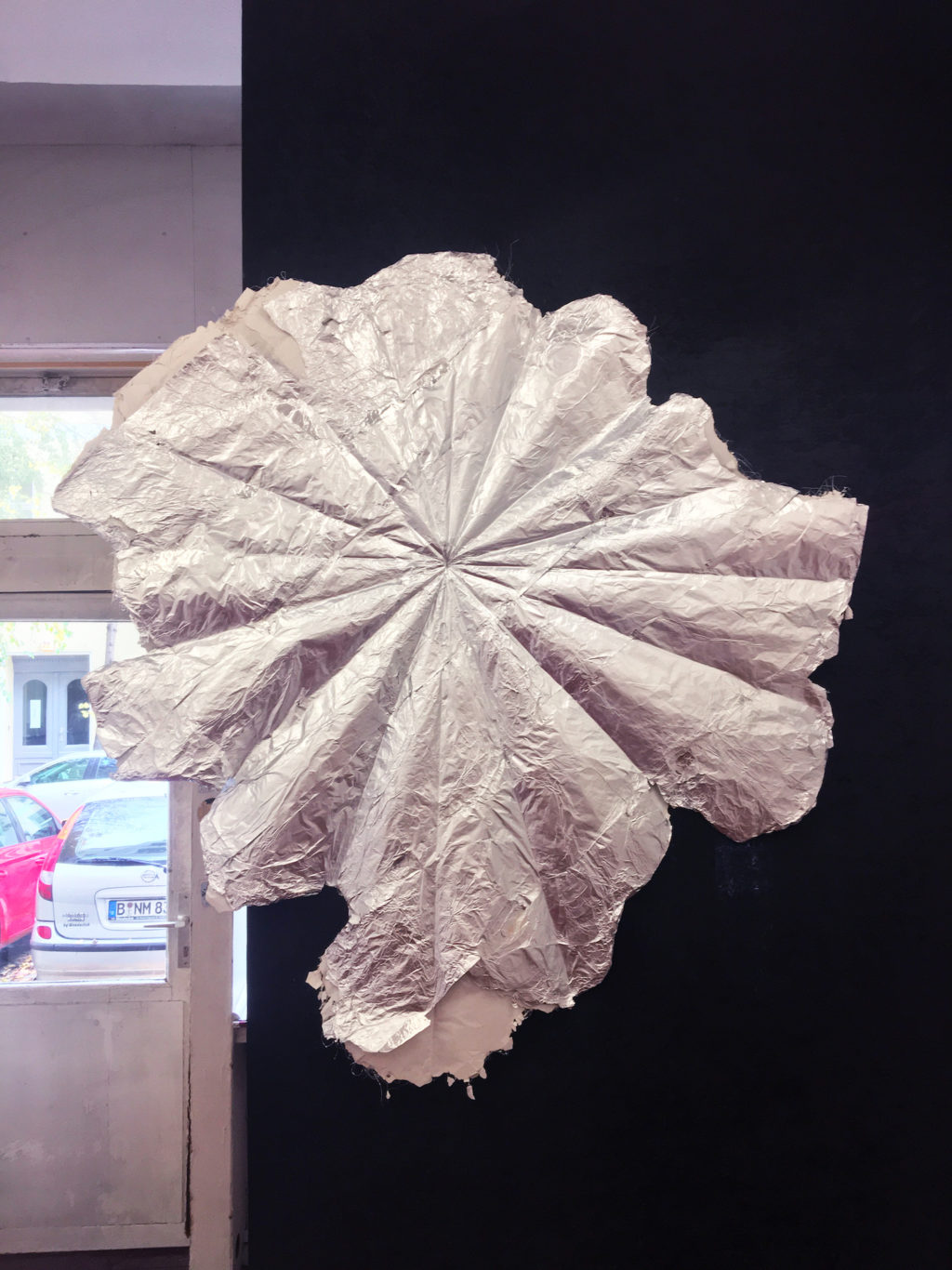

Rosa Joly’s work continually interrogates its own coming-into-being, beginning with its place of production - the studio. Taking as her point of departure a sense of uncertainty in the face of a certain desire to inscribe art in time, Joly deconstructs the authoritarian process inherent to conservation. She develops an economy of actions and participation that refuses any attachment to permanence in favour of a vision that is more fleeting, but also as political as it is poetic. To do this, Joly constructs material assemblies, whose visual impact is rivalled by their instability. Take, for example, the large-scale transfer of the entry hall of a building in the Hansaplatz of Hamburg that gave way to a brothel (Minnie Town, 2015) on entire sections of silk in oil pastel. Or even the free-standing structures in plaster and aluminium – an open means of sampling the real and/or consolidating an interstice that both reflects the immediate environment and transposes the underground heritage of the Factory into the Triangle France residencies at the Friche Belle de Mai (Shield, 2021). How can we define the status of this medium of transhistorical mental projection? Joly draws on sculpture, photography (through the technique of cyanotype), film, video and even text and emotional inventories of her work and living spaces. She submits them to test of geographical displacement, thus reconstituting in the exhibition an emotional climate, in which the markers of the initial place find themselves floating – like a Wild West saloon emptied of its affects. In this way, her work constitutes unipersonal cartography, through which she pays homage to number of cities, including Marseille, Hamburg, Lyon, Berlin, Paris, Los Angeles and even New York. On a micro-local level, she includes places or “rooms” shaped by the friendships cultivated in these places. In this way, Rosa Joly invites us to discover sharing, and above all giving, as a new materiality of the work. ‘Sharing’ not only evokes a sense of voluntary action, but also acts as an invitation to abandon, or even to put yourself in the care of another.

ARLÈNE BERCELIOT COURTIN Your work often appears as a tangible form of homage to other artists, be that through marking a connection to a title and/or a certain reflexive protocol. I’m thinking particularly of Matt Mullican but above all of Jutta Koether. As we were preparing this interview, we both mentioned Jutta Koether’s seminal work The Inside Job (1991), in which she deconstructs both the semantics of the studio and painting as a machinery of art discourse. On this subject, she revealed in an interview with the art critic Benjamin Buchloh: "BB: But your response to painting was not necessarily to resurrect it. Was there no attempt to redeem painting? JK: Yes and no. Redeeming was certainly not on my agenda. I never looked at painting as some masterful thing one would want to reinstall, but instead as a platform, a potential, an island, a lifeboat, a discipline to negotiate life . . . a performance. An attempt at something impossible, a reinvention of painting through painting. I wanted to make it a temporary site, which I took literally. There was this large painting I made in 1992 called Inside Job. It was a work that I made in New York before I showed in a gallery. I placed the painting in an apartment on the floor and invited people to view it."1, 2 Can you tell us how these two artists have influenced your perspective on art?

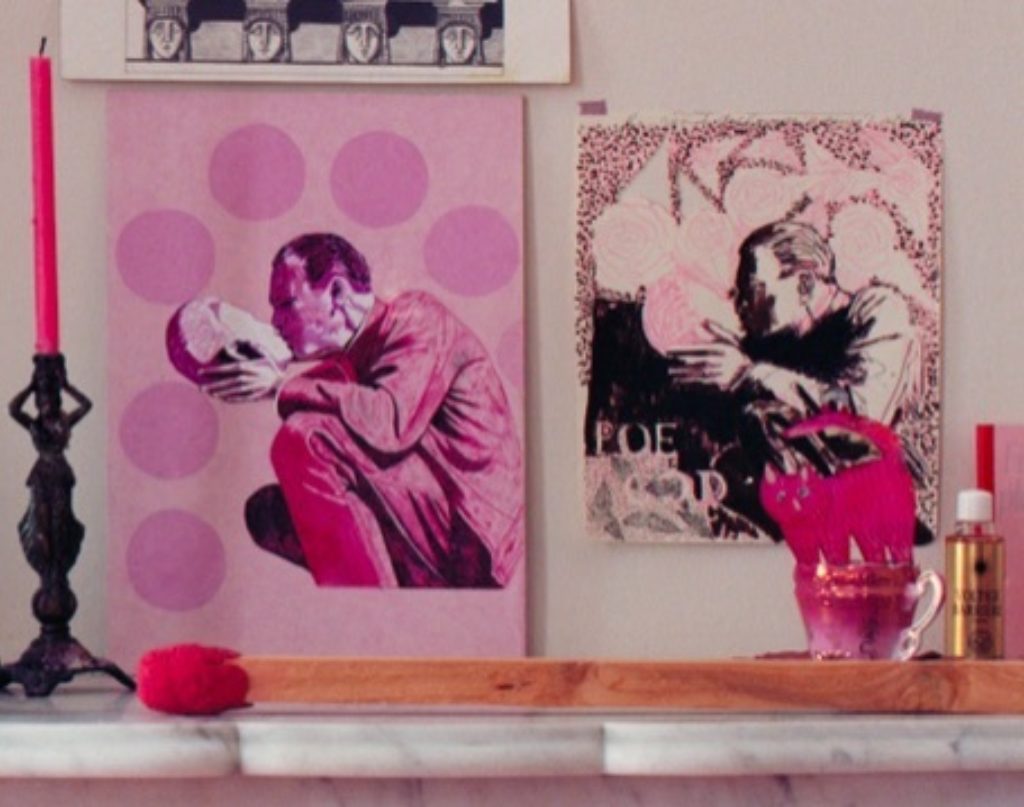

ROSA JOLY A bit like Jutta Koether when she constructed Inside Job, I envisage all my installations as social places or, in other words, as sites for sociability. That’s what was at the heart of my first solo show paris a scenario for a silent movie (2016); I took the title from a poem by Piero Heliczer. On that occasion, I exhibited for the first time a danse macabre, inspired by the Totentanz in St Marien’s (1463), which was destroyed by the bombardment of Lübeck by the Royal Air Force on 29th March 1942. The Totentanz chapel, also called Totentanz Kapelle, was reduced to nothing. In the bombardment, the danse macabre painted by Bernt Notke disappeared. This chef d’oeuvre, of which we only possess black and white photos today, adorned the walls of a chapel that contained an organ for the danse macabre. It was a historic organ that was played by Johann-Sebastian Bach. There was also the oldest flag in the world, which was a Danish flag. The exhibition paris a scenario for a silent movie, at Pauline Perplexe in Arcueil, is a sort of restoration of this disappeared painting. Except the skeletons, which were initially the links in the macabre chain, became very large cyanotypes on paper, and the portraits of notables and villagers are instead portraits of my friends, who are all artists living in Paris. Through this work, I assembled a form of resurrection and/or homage to a destroyed painting, but above all I produced a portrait of the milieu and/or artistic scene in which I participate and whose members modelled for me. They submitted to long posing sessions, during which we gossiped, shared deep secrets, napped, or surfed online.

I also really like to see the photos of the opening, where the bodies of visitors (of other artists and/or curators – principally people linked to the artistic scene) appear in front of this large fresco, and so multiply the farandole effect. Sometimes, they also took photos of themselves next to their paper doubles... These photos, which I do not necessarily show, are nevertheless part of the work and are very dear to me; as often in my work, time undefines itself, becomes superimposed, or even collapses into itself. This very spontaneous construction led me to produce, a few days before the exhibition, a number of portraits in oil pastel that were entirely orientated towards the moment when the living material of the drawings would be animated by the physical and social presence of the public, during not only the opening, but also the duration of the exhibition.

I’ve since found other “tricks”. For example, spreading out mirrors in the space of the exhibition to capture that driving energy provided by the bodies of spectators, so that the work itself is enriched by the life that traverses it. In Jutta Koether’s practice, it’s the notebook that records the passage of visitors and is nourished by not only the comments of actors from the artistic milieu, as reported by the artist, but also by her own life and her interactions with city of New York, exhibitions that she is going to see, objects that she finds whilst window-shopping or visiting a flea market... The work is a centre from which lines are launched, hoping that something will rise to the surface, still quivering with life, immortalised in three lines and/or strokes of oil pastel...

This spontaneity in attempting to capture a series of instants, to reveal an intimacy, a fantasy, to make manifest power relations, is also a way of battling against the sometimes oppressive aspect of “the work” that appears in a single block, which sets itself up as the product of a single individual who is a bit of a genius or a bit cool. Someone who, if it’s possible, will in passing trample on friends in order to appear as “the only one”... Another way for me to battle against this effacement of borrowing and inspiration is to always precisely reference my artistic family, whether they are living and/or of my generation and/or older, but none-the-less active. In the exhibition at Pauline Perplexe, in Arcueil, there was a copy of The Tide Inside (2015) - a story that I wrote and self-published. It compresses and condenses the notions that I just evoked; that is to say, citation, homage, destruction/reanimation, almost mouth-to-mouth... The story brings together Jay DeFeo and Marthe Bonnard, a famous bather and wife of the well-known painter, in a scene swimming in the Mediterranean. This scene is directly borrowed from a novel by the American writer Jane Bowles (Two Serious Ladies, 1943). In the Jane Bowles’ novel, the scene takes place in Panama (and so in the Pacific Ocean) between a sex worker called Pacifica and an American woman on her honeymoon. The apex of my story is this swimming scene, and then it descends back down to an anti-climactic ending... In the epigraph of the story, which is already well populated by references, characters playing against type and real-life personalities, there is a poem from the collection The Walls Do Not Fall (1944) by HD. She wrote the poem during the Blitz in London and it begins “There is a spell, for instance, in every seashell”. It’s magnificent. She compares crustaceans to a “master mason”... It seems to me that the question of being inside or part of a milieu is a bit like that, both in the real and figurative sense. It’s how we invest in or construct ourselves a house in order to shelter our soft, vulnerable bodies... We all have slightly different bricks, affects, educations, loves of literature, television, cinema or music, landscapes... These save us and allow us to feel in communion with another, who seems to think and love like us (or very differently to us...) There is thus this question of the shell that creates a place from which we can decide whether to let the other enter or not, with the consequences that can entail... My installations are often an external projection of this interior space. A space that I try to structure by creating walls and/or obstacles that divide the space and impose themselves on bodies, as if to include them in my project of transmission (of an affect, a reference etc.)

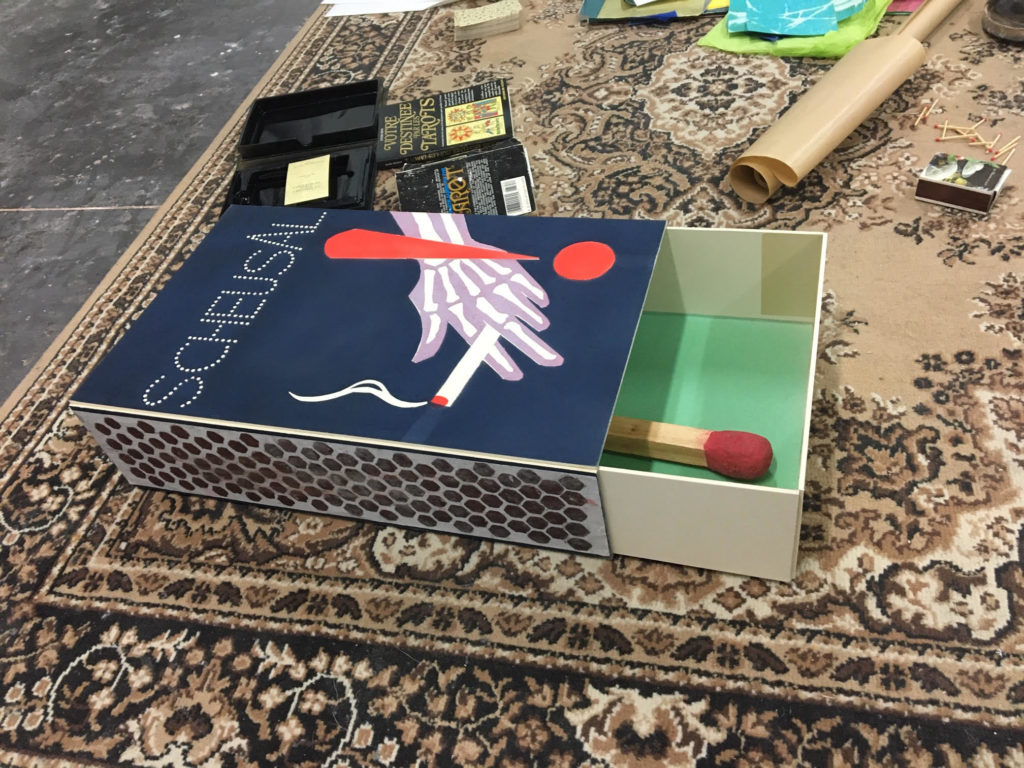

ABC This makes me think about what you told me about Sylvia Plath and your experience of reading her novel The Bell Jar, which she published under the pseudonym Victoria Lucas a few months before her suicide. In this novel, she describes a scene with a box of matches accidentally left behind by her doctor. This brings me to your work Rat Bastard aka Sleeping Child (2017), which is reference/homage to both Sylvia Plath and the work of Matt Mullican. Can you tell us more? It’s also interesting to note that you often focus on writers of poetry and/or short stories that turned their hand to novels. I’m thinking here of Sylvia Plath of course, but also of Jane Bowles, who inspired your own writing in the exhibition paris a scenario for a silent movie, and Eileen Myles in terms of contemporary literature. How does the relation between poetry and fiction inspire your own work?

RJ I read The Bell Jar a long time ago, when I was still a student at l’École Nationale Supérieure des Beaux-Arts de Lyon. I don’t really remember how I ended up reading it... In any case, it was a shock! First of all, there was this novel and then Sylvia Plath’s poetry that I discovered soon afterwards... In The Bell Jar, there is this passage that I love. It was the origin of the first giant matches that I made when I was a student in France. They weren’t functional objects, but “real” sculptures! In the passage, the heroine is left alone in the office of a psychiatrist. After he leaves, she goes towards the window and sees a little box of matches left there. She decides to open the box and finds that the tips of the matches are pink. She thinks that they have been placed there –intentionally – in order to study her reaction... I found this admission of paranoia very funny. And the liberty that the heroine takes by manipulating this object in an office that is not her own (I reread the passage and she finally decides to steal the box of matches...). I like the complexity of emotions that are awakened by this anodyne object. I have a really strong image of this little box in the middle of light and of the pink tips of the matches that reveal themselves – it’s a really beautiful image.

“After Doctor Nolan had gone, I found a box of matches on the windowsill. It wasn’t an ordinary-size box, but an extremely tiny box. I opened it and exposed a row of little white sticks with pink tips. I tried to light one, and it crumpled in my hand. I couldn’t think why Doctor Nolan would have left me such a stupid thing. Perhaps he wanted to see if I would give it back. Carefully I stored the toy matches in the hem of my new wool bathrobe. If Doctor Nolan asked me for the matches, I would say I thought they were made of candy and had eaten them.” (Sylvia Plath, The Bell Jar, 1963)

When I was studying under Matt Mullican at the Hochschule Für Bildende Künste in Hamburg, I exhibited my first prototype of a functioning oversized match. It was a sort of a “prop” that seemed sort of grotesque until its cumbersome tip was struck against a giant lightning strip and lit up... I remember that Matt Mullican really liked this “sculpture-prop”. Later, when he was invited by François Piron for a seminar at l’École Nationale Supérieure des Beaux-Arts de Lyon, I presented my research into the California scene of the 1950s and I activated a giant match to bring my presentation to an end. That day, I spoke about Jay DeFeo and the art scene in the Bay Area. In particular, I touched upon the assemblages made by the artists of that community in that period, especially those made by Bruce Conner. For me, it was an opportunity to ask Matt Mullican about his relationship to the scene in North California. He is from LA and much younger than the protagonists I was writing about. We then spoke about Sleeping Child (1973/2014), which is a really important work for me and remains a key element of his installations. I find it very simple (a piece of wood whose end rest on a pillow), but above all magnificent. I’m particularly touched by the simplicity with which he carries out his work and his capacity to provoke empathy...

This almost animist relationship to everyday objects, which are so common that they become invisible... It’s exactly what Georges Perec calls infra-ordinaire, “infra ordinary”, in his text of the same name (1989). For me, it’s the essence of the poetic, and thus of art. It’s something that touches me in the work of a certain writer, who has become really important for me in these last years and who I discovered far too late. Violette Leduc, who speaks with the specks of glitter that are prisoners of the concrete ground in the Paris metro, who wears a little fox fur that was found in the bins. She is never far from trash or the sublime. Above all, she writes the most beautiful pages on solitude and the company of objects.

“I will bring the heart of each thing to the surface. I will straighten myself up, I will live again. Since I am dead for others, I will abandon them also. Each time that I contemplate the box on my table, I receive a lesson in stoicism from it. The stoicism of each thing is not an interior contradiction, but rather an abandon that is held inside. If I went to prison, I would close myself up like a thing. Each thing is a contemplation that is held inside. In that world, like in the world of statues, there is an asphyxiating narcissism. Things that we do not move become soft wastelands. [...] I put the box on my divan. I lied down next to it. There is no longer any need for a common thread. We cleared the way, we exchanged the heart of our heart.” (Violette Leduc, L'affamée [The starving woman], 1948)

ABC In your research, two names are often brought together as part of the creative process. It’s the case, for example, in your films The Eye, The Asshole, My Sister (2019), The New Wounded (2015), or even Elbemini (2011). I wanted to share with you this attempt to define collaboration published in the work The Hundreds, co-written by the American authors Lauren Berlant and Kathleen Stewart. Particularly because they note that: “In any collaborative relation there is a fear of deep checking in. What do we do in the event of the force of clashing taste? It might turn out that we were falling through ice after all, not making tracks in the same- enough way. Some collaborators seek a secure job as the referent. The mind threatens to grow into an insane place if it’s not getting to feel how it was supposed to feel. Some collaborators demand that everything confirms the circuits of their enjoyment. (...) So we look for points of precision where something is happening. We don’t presume what’s going on in a scene but look around at what might be. We tap into the genres of the middle: récit, prose poem, thought experiment, the description of a built moment as in The Arcades, the Perecian exercise, fictocriticism, captions, punctums, catalogs, autopoetic zips, flashed scenes, word counts.” How would you define this desire to collaborate? How is it fundamental in your way of producing art?

RJ It’s in some way an extension of what I just talked about. Of what can appear to take the form of a homage (when it involves a more experienced artist and/or a historical figure), but which almost resemble an appropriation of certain aspects of works that I admire and which inspire me. The fascination that certain works inspire in me is what drives me to extend, transpose, interpret, and sometimes even upset the initial intention of the artist or author that I’m referring to. When I’m trying to describe what could almost be called “possession”, I think of the poet Jack Spicer and After Lorca (1957), which is a collection of fake poems and letters attributed to Lorca from beyond the grave, but evidentially written by Spicer himself. It’s a homage and it’s also an exercise in style; since literary pastiche, like forgery in painting, requires some talent! In the case of Spicer, the person making the pastiche is also one of the greatest authors... The figure of Lorca is a force that drives Spicer, who is enjoying finding the range of the voice of this poet that he admires. It’s both beautiful and irreverent, fundamentally serious and very funny...

“Frankly I was quite surprised when Mr. Spicer asked me to write an introduction to this volume. My reaction to the manuscript he sent me (and to the series of letter that are now part of it) was and is fundamentally unsympathetic. It seems to me the waste of a considerable talent on some-thing which is not worth doing. However, I have been removed from all contact with poetry for the last twenty years. The younger generation of poets may view with pleasure Mr. Spicer’s execution of what seems to me a difficult and unrewarding task. It must be made clear at the start that these poems are not translations. In even the most literal of them Mr. Spicer seems to derive pleasure in inserting or substituting one or two words which completely change the mood and ofter the meaning of the poem as I had written it. More often he takes one of my poems and adjoins to half of it another half of his own, giving rather the effect of an unwilling centaur. (Modesty forbids me to speculate which end of the animal is mine).” (Preface by Federico García Lorca / After Lorca by Jack Spicer, 1957)

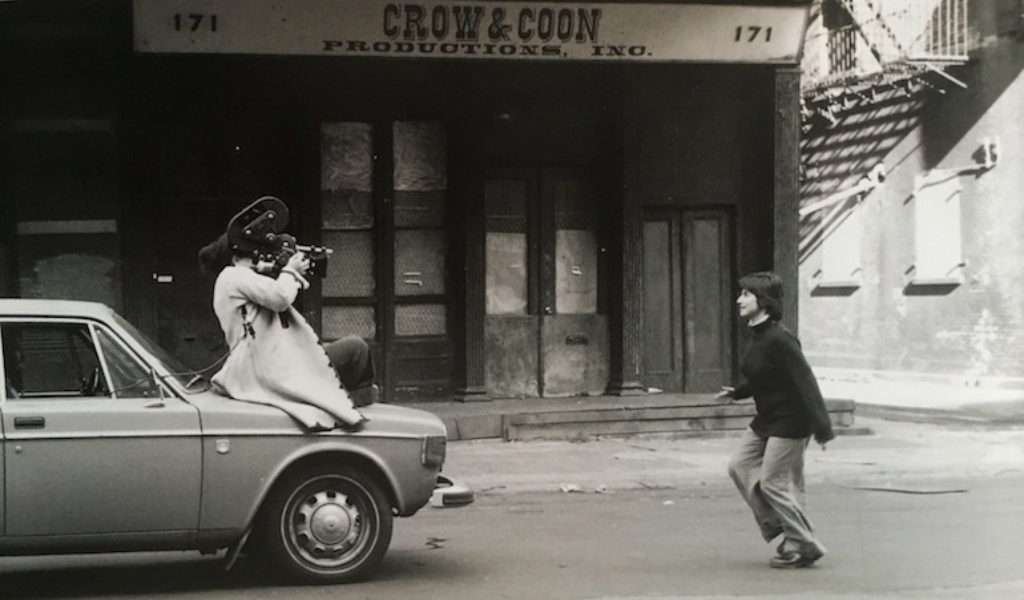

To return to your question – which I believe concerned more a form of shared work that is anchored in the present of two living and consenting individuals - I like to work in a little team, often “one-to-one”, with certain artist friends of mine, especially when making films. If we take the films that you mentioned, the visual material for Elbemini, for example, came out of a shoot with Daiga Grantina. The New Wounded (2015) was shot with Julie Gufler. My last film The Eye, The Asshole, My Sister (2019) was the result of a year working with Anaëlle Vanel. Each shoot resulted in an intensification of my relationship with each of these artists. The desire to find oneself, on one hand, and to abandon your own identity and melt into the other, on the other hand, produces these sorts of little miracles. Like those little moments of fleeting grace that film can capture; since its primary function is to record what we believe we are seeing, although in the end it is much more than that. It’s funny now that I think about it - each of these artists has developed a practice that is quite different from mine and they are also incomparable to each other. When I met Daiga, she was shooting films on 8mm. Julie is a writer and Anaëlle is a photographer. Working with them was essential to my construction of an identity as an artist. I loved coming out of the solitude of the studio, which can be a bit heavy, to let myself go in a project, whose exit escaped us... Letting yourself go is only possible in an atmosphere of absolute confidence. The fact that we are still friends and that our friendship was even strengthened by these shoots is, in my opinion, the proof that the inspiration was mutual and that each person found their groove!

ABC The physical object of film also often has a privileged place in your work. How has this medium become a key aspect for you? Among your references to cinema, we have already mentioned the avant-garde, both European and American. I’m most of all thinking of Chantal Akerman, whose film Je, Tu, Il, Elle (1974) we discussed, along with its autobiographical dimension. We also mentioned La Bande des Quatre by Jacques Rivette and its relationship to improvisational theatre. Or even, the films of Kenneth Anger, which really marked you. There is a certain eroticism in his films that we also find in how you treat the image in Elbemini (2011). How does you work share this same belief in image?

RJ The relationship between the image in movement and belief... it’s a good question! To begin my response with something a bit off-topic, I would say that films have the power to change my life, to deeply change the direction of its course... Films are very powerful objects. It’s clear in Kenneth Anger’s work, for example, that films are rituals to which he gives body, which follow a precise score, a choreography that is as active as it is invisible.

In terms of my own work, I would say that there are two aspects that coexist. Firstly, being a cinephile, that is what I watch and what inspires me, and secondarily my own experimental film practice. If I put this distinction in place - that is, if I put to one side the “consumer” (or even addict) aspect of the cinephile and to the other side, the production of my films - it’s only to underline that one leads to another, that certain films help me get a foot on the ladder and open up new horizons... For example, I discovered the work of Jay DeFeo at the Ludwig Museum in Cologne whilst watching The White Rose (1967). In this film, Bruce Conner captures the extraction of DeFeo’s famous monumental painting The Rose from her studio. This film acted as the point of departure for my research on DeFeo that has lasted more than ten years. Today my research is still concerned with her work. She is at the heart of my next film project, which will be exhibited as part of the first exhibition of DeFeo’s little known photographic work at la Maison Européenne de la Photographie in 2023. Bruce Conner and his films Looking for Mushrooms (1967), Cosmic Ray (1969), and even Vivian (1965) - without forgetting Crossroads (1976) - are key influences. Talking about the films of Chantal Akerman, it’s after watching News from Home that my friend Anaëlle and I started going out at night and hanging out on street corners to film our neighbourhood... At that time, we lived in Berlin near Kurfürstenstrasse. Unlike New York, Berlin is a city that sleeps. However, this neighbourhood is actually bustling at night, because of the presence of sex workers, their clients and also their pimps... The place and the moment are very different to what Chantal Akerman filmed in News from Home. Even if in her case, and in ours, there was a desire to film a foreign country at night, to set up your tripod and wait. Yes, the autobiographical dimension in Chantal Akerman’s work, the presence of her body even when it’s off-camera, the emotion that emerges despite the apparent objectivity of her very frontal framing of the image... I really like everything I’ve seen by her. Starting by Jeanne Dielman, 23, Quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles (1975), passing by Rendez-vous d’Anna (1978) up until Un Divan à New York (1996)…

In her feature film, Je, tu, il, elle (1974) that you mentioned earlier, and which we have spoke of many times, the body of Chantal Akerman is present throughout. From the beginning,

where we see her eat whole spoons full (or even 1kg bags full) of sugar, to the end where she

films herself making love to a young blonde woman, for whom she hitched a ride in order to meet. I’ve liked everything that I’ve seen by Chantal Akerman – so I could talk about her work for a long time –but I prefer to perhaps finish by returning to News from Home. It’s very beautiful to imagine her and Babette Mangolte crisscrossing the streets of Manhattan at night. For me, shoots are also a way of binding together friendship and work with certain friends, if they want that...

ABC We mentioned the important place reserved for the studio as place of work, the collaborative approach of your films, the interrelation between friendship and avant-garde cinema, but we should also discuss the research aspect that is inherent to your artistic work. I’m particularly thinking of Jay DeFeo, on whom you worked in depth during your doctorate in art research. How was this proximity with her work constructed? During our exchanges, we often spoke about The Rose (1958-66). It was the result of more than seven years of non-stop work, during which the artist covered the same canvas in thick layers of paint. In this way she transformed a simple piece of fabric into a bas-relief, or even sculpture, which was static - not only because of its weight, but also because of the fragility. Through this gesture, we can perceive a rupture with, or even a satire of, the flatness of post-war expressionist painting in America. It’s also a critique of the almost masculinist approach to this medium. Jay DeFeo was one of three women invited to exhibit in the famous show Sixteen Americans at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. She initially refused to present The Rose and then, even though she finally accepted to participate in this exhibition, she did not attend the opening. How is the political approach of Jay DeFeo in dialogue with your own work?

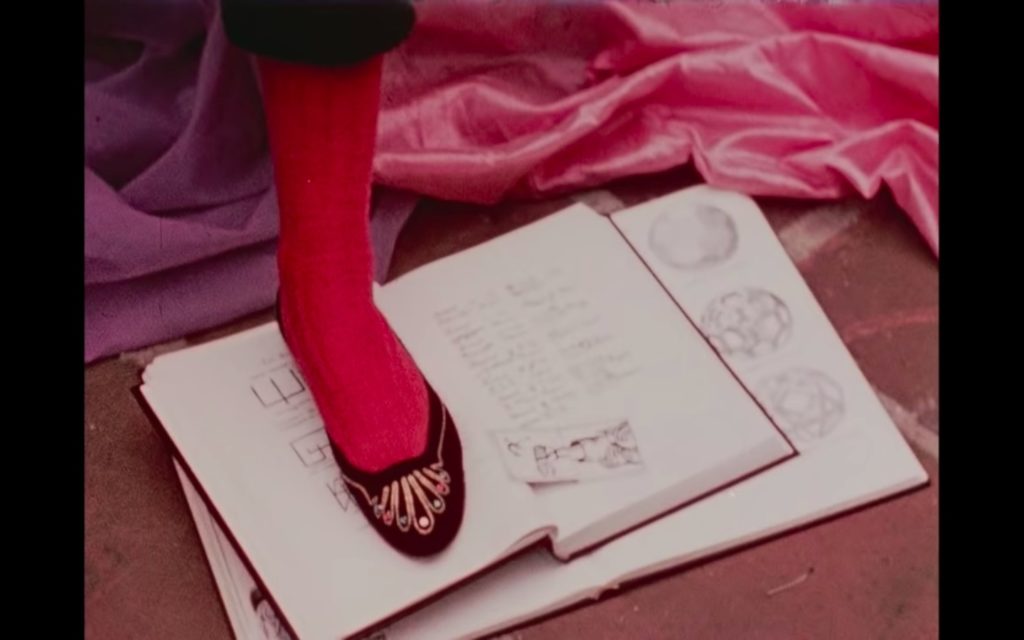

RJ If Jay DeFeo’s work is political, it’s perhaps through her unwillingness to compromise. This led her to dedicate herself, in the moment when her career was taking off following Dorothy Miller’s exhibition at the MoMa, to realising her vision and to letting herself develop outside of the “normal” proportions of space and time. The monumental painting The Rose (1958-66), which she refused to include in the exhibition Sixteen Americans at the MoMa and which many attempted to buy over the following years, became in this sense an anchor. A sort of flag for the community of artists and poets that gravitated around 2322 Fillmore Street in San Francisco. Rather than becoming the exception who extracts themselves from a particularly rich scene, where interdisciplinary exchanges were the rule, Jay DeFeo anchored herself even more solidly at its centre. By producing what seems like, at first, a sensation of being “on site”, she animates the centre. Sometimes, when I consider her trajectory and this crucial moment in her career - during which she decided to not go to New York and did not even respond to galleries that contacted her - I’m tempted to think that it’s a sort of self-sabotage and/or fear of being too much in the spotlight.... But The Rose is far from being a fearful and/or modest work. It’s rather an enactment of a deep belief. It’s also the creation of a sort of scene, in the sense of “stage”, paraded across by the curators, artists, and poets that visited her. Certain visitors to 2322 Fillmore Street have spoken of a chapel, at the centre of which she placed the concentric painting. In fact, it was placed at the centre of the bay window of the studio, which had no electric lighting. Like Jutta Koether’s The Inside Job, the production of The Rose participated in the creation of a site, or even myth. These two artists create the possibility of an irrevocable “here and now”, which attracts curious people to them from all walks of life. They do it very differently, but in both artists, we find painting as a reflexive space for deconstruction. The contexts are very different; Jay DeFeo spent almost eight years (1958-1966) producing this painting, which is as monstrous as it is performative.

ABC 5. Among the geographies of your research, the USA, California, and particularly the Bay Area, have a particular place. You’re currently preparing to return to Jay DeFeo’s archives thanks to the support of a number of funds, including Convention Ville de Nantes/Institut Français and Aide Individuelle à la création de la Drac Loire Atlantique. How does this artistic territory interact with your work? What are the documents that you are hoping to access? The politics of conservation in the USA is very different to that of France and Europe, how does that facilitate and/or complicate your way of working on site?

RJ The upcoming journey, which has been long delayed due to the pandemic and the closure of American borders, will be my third visit to the Jay DeFeo Foundation. During my first visit in October 2017, I discovered a quasi-unknown corpus of DeFeo’s work - a whole continent of photography that I didn’t know at all and that remains relatively unseen today. During my second visit in July 2018, the Jay DeFeo Foundation generously assisted me. I was able to spend two weeks in Berkley consulting contact sheets. I was also able to access sublime prints made by the artist in the beginning of the 1970s. Without entering into too much detail, I can say that this corpus is made up of virulent vanities, chemical phantoms, and threadbare objects that are captured in their survival against the odds. Whilst remaining a little vague and enigmatic - to above all not ruin the effect of the magnificent exhibition that is being prepared at la Maison Européenne de la Photographie in Paris - I would nevertheless like to underline that this photographic work has enormously influenced my own work over these last years. I’m impatient and excited to return to Berkley to film a selection of these prints with my 16mm camera... I can also quickly sketch the context in which these photos were taken at the beginning of the 1970s. After the adventure of The Rose, a divorce (she had been married to the artist Wally Hedrick) and being evicted from her studio on Fillmore Street - as well as the exhibition of the tableau in Pasadena in 1969 and its storage in the San Francisco Art Institute, where it would remain for more than twenty years - Jay DeFeo stopped making art for almost four years. During this time, she hung out with a group of young deserters from the war in Vietnam. They hopped between rock festivals, which were numerous in San Franciso during the end of the 1960s. Her photographs, which will provide the primary material for my film, were taken at the moment when she returned to work and began to assemble pieces of a past life. She documented works saved from her move and teeth that fell out one after another, due to her prolonged exposure to the lead contained in the white paint that she used to give life to The Rose ... I want to shoot these prints, which came out of a return to producing work, front-on. A bit like a homage in the same vein as Curtis Harrington’s The Wormwood Star (1956), which includes drawings by the artist and occultist Marjorie Cameron. Or even in the image of Kenneth Anger’s The man we want to hang (2002), in which he films an exhibition of paintings by Aleister Crowley.

I’m also really happy to share with you some images of the exhibition in which I’m currently participating in Berlin, in a new space founded by Sebastian Wiegand on October 23rd. For this exhibition, I produced a duo of sculptures in plaster and aluminium, according to the technique that you mentioned at the beginning of our exchange. One of them is called The Wormwood Star, in reference to the Curtis Harrington film... It seems to me that here we have reached the end of the cycle...

Translation: Bea Bottomley.