A Conversation on NO SAFE PLACE by Peter Brandt.

A conversation about NO SAFE PLACE by Peter Brandt.

9th December

Aurélia Defrance invites Won Jin Choi, Sophie T. Lvoff and Aurélien Potier to react to the artist publication No Safe Place by Peter Brandt.

No Safe Place includes images of Brandt's artworks produced as part of his 'Post Trauma Documents' series, as well an essay on 'The Forensics of Trauma' by curator Jeppe Ugelvig, and conversations with author Thomas Lagermand Lundme, and theater director Iben Hendel Philipsen. The book addresses the subject of trauma and the process of healing, and emerges from the artist’s own experience of being the subject of a violent attack. The publication investigates why healing can be such a difficult process, and how society places emphasis on the perpetrators of violent crime rather than on the victims. It argues for a forensics that embraces immateriality, artworks, aesthetics and even literature as evidence.

The Winter Office presents this publication in the frame of 'Nature as Infrastructure', and thus proposes to draw parallels between trauma and climate change. With this in mind, the Earth could be thought of as a body subject to violence, and as such, climate change could be considered as evidence of the Earth’s experience of trauma.

Aurélia Defrance has been invited to circulate this book among Marseille-based peers. Won Jin Choi, Sophie T. Lvoff and Aurélien Potier all received a copy of Peter Brandt’s publication. While in conversation with each other and using text based material, they will tackle the notion of trauma and the position of the victim.

No Safe Place Peter Brandt Really Simple Syndication Press Copenhagen, October 2020

No Safe Place by Peter Brandt can be ordered here (http://rssprss.net/)

___________________________________________________________________

A CONVERSASTION about NO SAFE PLACE by Peter Brandt With Aurélia Defrance, Won Jin Choi, Sophie T. Lvoff and Aurélien Potier

Aurélia Defrance: Hello everybody. Thank you for accepting this invitation to share your view on the book ‘No Safe Place’ by Peter Brandt, published by Really Simple Syndication Press. This book was originally going to be presented in the frame of an exhibition and public program proposed by The Winter Office for the artist-run space Adelaide. As the project had to transform into a virtual program called ‘Nature as Infrastructure’, Hugo Hopping, from The Winter Office, asked me to circulate ‘No Safe Place’ in Marseille, also as a way to activate its physical presence, and give an entry point to the book. So, here we are to exchange about this together. Won Jin, do you want to start and share your reaction when discovering ‘No Safe Place’ by Peter Brandt?

Won Jin Choi: The first time I read the book I didn't have a specific reaction towards it. I understood what Brandt is talking about, what his work is about. The second time I read it, everything started appearing very personal to me. Emotionally and mentally. So my final reaction about the book was more of a frustration. I didn't feel uncomfortable reading about it but was confused about making a clear choice of an approach to this conversation. So I will have to see how I feel about this today and sort of… go with the flow.

Sophie T. Lvoff: As soon as I opened it and started reading through it, I was kind of dreading the idea of something we discussed together before, the elephant in the room, the fact that we're dealing with somebody who is a victim-survivor as a white male, whereas a lot of the other research I've been doing and conversations I have, and interests I have, are with people who are not; not the white male being in a place of victimhood.

And so I was dreading how to wrap my mind around it. But at the same time I think he makes a lot of arguments and a lot of space for his rights, his processing of this attack. There is one part in the book where he explains how everybody was saying how lucky he was that he survived the attack. The idea that the world is by de facto nonviolent for him as a white man, he doesn’t have to walk around scared that he’ll be shot by police or sexually harassed or objectified, but actually in everyone else’s mind, it is violent. This idea of luck and violence, it's relatable to many people. But he questions this idea of luck in the long-term, that he now has to live as a victim.

Aurélien Potier: I also wondered how to relate. Questioning if I wanted to speak personally. I also think one of my first reactions was to feel slightly angry and frustrated when reading the book. For similar reasons that Sophie said I believe. At the same time, Brandt addresses these issues of legitimacy in the interviews, the fact that the audience would question his testimony. Going through this book, one of the main questions in my mind was revolving around the exterior reactions to the victims discourse, a discourse that is often dismissed. In the first essay, it is discussed that the victim discourse is hard to hear because it is so extremely personal. In his essay, Jeppe Ugelvig is talking about Derrida, he says, “The shareable and shareable secret of what happened to me, to me to me alone, the absolute secret of what I was in a position to live, see, hear, touch, sense, and feel”.

AD: It also raises the question of ‘who is speaking?’. Why would we be more keen on receiving a testimony that is told by somebody else than the victim? Something that is also addressed in the book is how we give more value and importance to scientific evidence, which is approved and represents authority, leaving apart the embodied and emotional evidence. So a testimony as evidence raises a set of problems. And it seemed that you all saw the autobiographical and personal aspect in this specific case as an issue. Won Jin, you said it made you want to step back from it almost?

WJC: Yes, I had to step back a bit. If I cannot entirely detach myself from the book, am I really going to open up and talk about my personal experiences? Do I really want to do that? Is it necessary? There was this kind of strong invasion of intimacy or privacy that I felt when reading, almost as if the book was revealing my personal secrets. This was something very strange to go through. And I think that’s one of the reasons why it took some time for me to digest it.

AD: But do you think it's because the book is engaging you or asking you to share something personal? Or can you relate differently, as a viewer?

WJC: Yes, it can be possible. There were some parts of the book that I could relate to personally. Essentially the feelings associated with the trauma and at what point we actually decide it's a trauma. There were some recent and tough events that I had to go through, and I think at one point I decided to not consider them as a ‘trauma’ because I chose not to be a ‘victim’. Even previous physical aggressions from strangers I have experienced, each and every time I would tell myself to refer to this as a non-traumatic experience and categorize them more as an unfortunate event even though the shock, anger and feeling of injustice of receiving unnecessary violence was very present, in order to ‘move on’. Then reading this book made me look back to all the past events that I thought I had somehow erased, I finally started recognizing the real issues in them and acknowledging that maybe these are now part of my trauma. So from which point and which state of mind do we actually decide it's a trauma? I started to question a lot of things associated with that.

STL: In the conversation with Tomas Lagermand Lundme, Brandt mentions that trauma only exists in the aftermath, in the afterwards of itself, on a psychological level. And then in the introduction to I Died In Italy But No One Knows It, Brandt writes: “I was in possession of an intense scrutiny of myself and my ‘issues’ [from doing this rehab]”. And so, in Brandt’s case, he decides to process the trauma and deal with it, that there is no escape. If you're consciously making the decision that this is an unfortunate event that happened to you, like Won Jin did, you have a different personal power to decide that you won’t engage with it, you compartmentalize to survive. Brandt rehabilitates to survive. In thinking about the title of ‘Nature as Infrastructure’, perhaps we can also say ‘Human nature as infrastructure’. Brandt has stayed with his trauma for years and years. These are examples of human nature that provide a structure for how to live.

I think it goes back to a cultural question too, and a luxury of self-care. An example I think of is Niki de Saint Phalle, as an artist with a striking aesthetic associated with her, and someone who was dealing with trauma. She was raped as an 11 year old by her father. She didn't have that publicly known until 50 years after it happened, when she wrote an autobiography, saying my father tried to make me his mistress at the age of 11.

And I was just reading this New York Times article with her in the Home section, not quite real news, but it was in the 90s, and she also mentioned her rape. But in such a breezy, easy statement… saying that you're raped at the age of 11 by your father, and just move on to ‘oh? How was your lunch?’, it's just a different approach entirely. Although we do see a body of work from her that is responding to things that she's scared of and things that haunt her, it's not this kind of interrogation that Peter Brandt has allowed himself or been entitled to do.

But one problem I had going through the book, is that I found that it was so versed in a dispositive of contemporary art that I had trouble with some of the decisions visually and aesthetically. Like in the work ‘Order of Empathy’. This is very much for me a reference to Eva Hesse, a kind of ephemeral sculpture building with minimalist land art sculpture. It's perhaps unavoidable that his references are these art historical references versed in modern and contemporary art, because this his metier. But for me, it gets complicated to try to push against this label of ‘art as therapy’, when it's always going to be versed back into an exhibition making, or done in the context of international residencies, which he talks quite often about, while using the tools of art therapy. And so you're like OK, what is your goal here?

AD: It makes me think of the artistic strategies used by Brandt and other artists to translate a trauma into a work. And how much an artwork which acts as evidence needs to be ‘literal’ or rather, readable. In that sense, ‘Order of Empathy’ is way more abstract than Brandt’s earlier works, where the trauma is made explicit. But does an artwork have to be less direct to engage the viewer?

STL: Something that I really loved about the description of textile in Brandt’s work is that it is described as “a material carrier of memory,” and this in relation also with the AIDS quilt’s reference inside the first essay by Jeppe Ugelvig. I felt that in the later works, there's like stringy, bands of fabric that are quite different. In ‘In Mourning and in Rage’ (2016 - 17), I think this is my favorite work in the book, it's a work of two-sided banner with applicated fabric embroidery, oil paint, pearls, pencil, wood, and garbage from the crime scene sewn into the fabric. So you have literal evidence or material from the crime scene, but it's abstracted and it's layered without explicit text. For me this holds more, it's less didactic (for lack of a better word) or it's just less explicit and it allows for somebody to want to wonder. Whereas the literal handwritten hand painted words drive your reading of the work.

AD: Aurélien, is it specifically the earlier works which triggered your reaction?

AP: The frontality of the earlier works triggers a feeling of bluntness that can be hard to deal with for the audience, it can be overwhelming. I am bound to question frontality and legitimacy. Which leads me to how the work is received, since we are actually discussing an artist’s monograph, a synthesis of many years of works.

Brandt also mentions how he has been criticized for benefiting from his aggression, in the way that he is using it in his artistic practice. To which he replies : don't you think I would have been able to come up with other subjects in my art? which is a valid point. But I have to recognise that despite this claim, I still kept in mind him benefiting in terms of his career. Which made me strongly question my own reaction when going through the book.

STL: I don't feel jaded about his choices in his career, because it is just the way that he is able to find meaning from this. And he says “[I found] understanding in the incomprehensible deal with the meaningless.” I think that's actually a universally sensitive approach for artists : How do we understand these things that happen, in this violence, in this modern world. That redeemed it for me, this final dealing with meaninglessness or trying to understand something incomprehensible.

WJC: I really started questioning the explicitness that comes from a cultural difference. I recently reread unsent letters that I wrote to various people when I was experiencing a difficult time, and I found myself expressing myself in a very passive way. I would never directly write about what happened to me. It seemed like I was trying to focus on describing my feelings in a most abstract way, and nothing was concretely there. I found it extremely uncanny. There were ten different letters addressed to ten different people. Noticing this common indirectness in all circumstances made me question Brandt’s way to express himself, and his specific choice of explicitness. So I wondered, does the difference that comes from a cultural background apply to this? Although I didn’t necessarily have a hard time understanding the content of the book, somehow I was constantly chasing after the clues.I had to ‘deal’ with the book several times to be able to comprehend why the trauma had to be materialized, to be shown.

STL: This Western European process of the self that Brandt went through via his brain rehabilitation and intensive psychotherapy, seem also so far apart from another place. You wonder how that process would be in Japan, in Korea, in Brazil, in Morocco. To take oneself out from any given community, to work on the self. It's also quite privileged, and time consuming (laughing).

AD: I would also like to discuss how you relate to some of these questions in your own practice. Aurélien, text is central to your work, and you also include personal elements that you sometimes fictionalize in your writing. How do you relate about basing your work on your own life and your own self?

AP: Yes, there are, in short, notions of intimacy and vulnerability in my work. And it is true that I also very directly write personal things. However, Peter Brandt mentions how important it is for him that the work is as close as possible to authentic. The notion of authenticity seems really important to him, which is something I differ from. I lie a lot. The lying, the manipulating and the simulating are very important for me. As a way to navigate, resist, also relating to different forms of violence.

AD: But the fact that you lie doesn't mean that you remove yourself from the work. Was that a clear decision you made for your practice?

AP: It's building up. It's something that happened in the work, that I realize I am more and more interested in. If you lie, you create another reality. The more you lie, the more realities you create, you multiply paths and layers of possibilities. Lies can depart from “real” events or be completely made up. In both cases, it is a strategy to lose myself, so that others would lose track of what I say.

AD: Sophie, your practice unfolds through writing, sound, sculptural and performative elements, but first of all through photography. Do you want to tell us about how you relate, as a photographer, to this idea of an artwork as evidence, as coined in the book?

STL: It brings us back to the question of authenticity, and how I aim to photograph in relation to a place as an out-of-towner. I question the encounter, and how to capture a place I photograph. What does authenticity mean here? In another vein, this idea of photographic evidence was something that I really thought about and responded to immediately. When going through Brandt’s book, I immediately thought about this project of two artists in the 1970s: Larry Sultan and Mike Mendel, called Evidence. They went through these very dry administrative archives of photographs from corporations, from scientists, from technical schools, and went through thousands of images. Sultan and Mendel picked out ones that made a strange narrative and links between images, spreads in the book, and simply titled the book “Evidence” and you're wondering if it's authentic. There are photographs of people looking in giant holes in the ground, there is one where there is a horse hoof on a scale and a scientific calculator next to it. There are explosions... and so you wonder, What is this evidence of? It is a recontextualizing of these technical photos, that are deemed evidence because they said so. The authenticity and the purpose of these photographs is totally taken away and it's given another authority. Susan Sontag wrote about this, about the idea of captioning photos in her essay On Photography. How adding context also gives or takes away clues and authenticity. You can say anything you want about a photograph, and it becomes evidence. This is something I'm always interested in.

And Evidence is very much a photographer’s photography book, it’s an object that I’ve coveted since I first bought it for myself. If we look at Brandt’s book as an object, I’d like to bring up the fact that it’s covered in a type of skin, in Brandt’s self-portrait as a bruised and battered man, in a mirror. I thought immediately of Nan Goldin’s The Ballad of Sexual Dependency, and it’s another type of bible of photography books. The decision to use the photograph printed directly into the linen, then stretched over the cardboard skeleton and meat of the book, works very well for me after a thorough read of the book. As a cover, I wasn’t sure how it was going to be resolved, but it needed some time to grow on me.

Also when Brandt mentions he wanted to make his “Nan Goldin photograph”, he refers to her photographing herself with a black eye, and that he failed at doing this self portraiture: it’s blurry, he’s obscured by the camera, it’s illegible. I liked his bluntness about failure: the failure of his body, the failure of his photographs, the failed body as being beat up. I love the idea of failure in a work.

AD: Could you reflect on ‘No Safe Place’ within the context of the programme ‘Nature as Infrastructure’ and link it to some of the approached issues, such as the human impact on the planet?

AP: Well, this is how this book was presented to me. When you gave it to me, you introduced it as part of this program ‘Nature as Infrastructure’. So going through it, I had this title in mind as well. Most of the questions and my own reactions to the book were related to the positions of victim and perpetrator and how we make sense of them, also when relating to the violence that the Earth is subjected to.

STL: There’s this really poignant part where Brandt writes, “And what about the Earth? Is the soil stained not only by the assault on my body but also the blood of other victims of other crimes?” And this very personal thing then turns into a universal act of how much violence and pain the Earth can hold I mean, this is poetic in a different (un)quantifiable term than climate change, but it's the venue for all of this to happen I would say. The Earth being that venue. And the fact that Peter Brandt is putting a stone, soil and other things from this site, as pieces of actual material evidence that witnessed his assault into a sculpture, into an exhibition space. I think it's an interesting way to grasp at validating the experience. He also mentions in the same page (160 in the book) Trump winning the election while he was in Rome, so you have this statement that a world order based on empathy was indeed a utopian fantasy. So this idea that you can have empathy through all of the things that he's talking about is not possible when you have this new world order.

WJC: I started questioning a lot about the damage, the contamination, and the recovery. Those were three keywords that popped up in my mind when I was trying to put the book in relation with Nature as Infrastructure. Once something is contaminated, with a given damage, does something called ‘full recovery’ exist? The current pandemic has been a moment for me to realize several things including my personal thoughts on ecology because I often took things for granted - relationships with others, health but my relationship with nature in particular. The current pandemic context has made me recognize the shifts made in the social context and the effects on our way of living.

AD: You also mentioned curatorial choices you made in this context with Belsunce Projects, the project space you are co-directing. A slowing down instead of keeping up the rhythm of the production of events, can you talk about this?

WJC: For me it is very important to create the experience of having direct interaction with the public and with the artists in terms of exhibition making. This year has been complicated but the question of how to maintain gatherings of artists and public inside and outside of the space was inevitable. We wanted to honor the initial intentions of physical, direct interactions that must be present, especially with one of the projects that we have been working on since before the first lockdown. The exhibition space will transform into a free copy center, welcoming the public for three weeks for different workshops, performances, engaging in an auto-editorial practice in collaboration with the local community. Rather than cancelling, we are working on finding alternatives on creating an environment to adapt to the restrictions that we have to face to be inside of the space. The current crisis has not only directly affected this project, but other exhibitions we have planned for the coming months are now requiring further planning. Eventually, slowing down is completely necessary in this entire process.

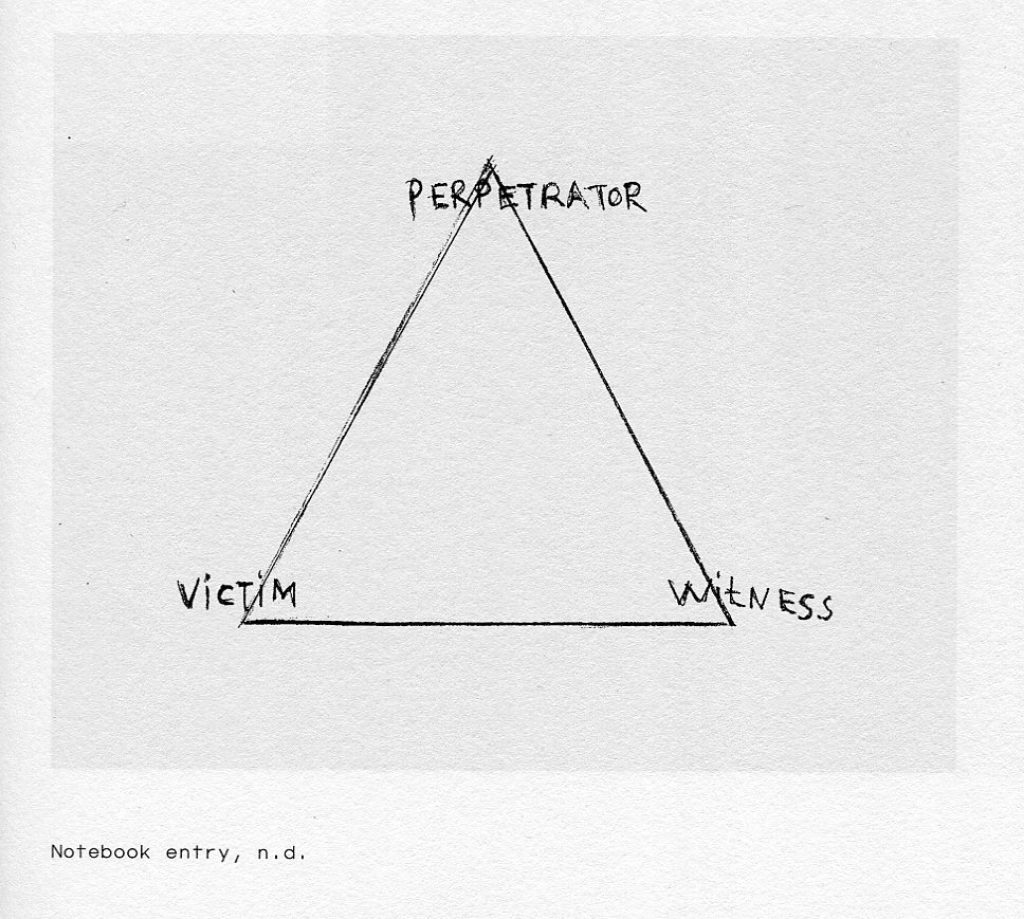

AP: To come back to the notion ‘Nature as Infrastructure’, relating to ‘No safe place’. Very central to the book is the triangle schema of perpetrator-witness-victim. So far we talked about it as ‘we are the perpetrators’ and the Earth is the victim. I was wondering...is that so? Who would be the witness then? Who does enter in which position if we want to relate the notion of victimhood to nature?

AD: Who do you mean by ‘we’?

AP: I think human beings.

AD: No matter the age, the job, the way of living? Humankind as a whole, or should we start differentiating, in order to reconsider this triangulation as you are proposing? Would you agree that some humans can be more witnesses or victims than perpetrators, and also that the Earth is not only victim but first of all a witness? Considering the planet as a victim of mankind can be a way to give continuity to its will to dominate nature, no? The Earth is gonna change, transform...

STL: And explode… in 300 millions years.

AD: But from our actions on it, we will be our own victim.

AP: Yes, that's what I wanted to address. We angled the conversation with the idea that humankind is hurting the Earth. But I think that this is way more complex. I was wondering what would happen if we shift perspective on these perpetrator-witness-victim positions, where the perpetrator is the activator. We could explore nature not being something outside of ourselves, and therefore not necessarily in a different “position” than us.

STL: It makes me think of the artists who have been poisoned by their work and who have died from literal toxicity of their work. I keep going back to Niki de Saint Phalle, who suffered from terrible asthma and breathing complications after using toxic plastics to build her work. Eva Hesse, another person I mentioned earlier, had cancer after using these kinds of really horrible materials. And so, this relation to Earth, and maker as perpetrator and witness and victim are all encompassing. I don't know if these people are martyrs or sacrificed for making their work, but poisoned by it.

I am also thinking about the act of burning because the only clinical, technical evidence that Peter Brandt had were these medical records that he ends up burning and using as a work of ashes in a jar. And that’s very metaphorical because, we can talk about Australia and the American West burning at an incredible rate in the year 2020, but things rise from ashes right? That's how you rebuild forests, and there's an example of Chernobyl, which has reforested after the incident because the earth can grow back from fire, and with no human presence, it can heal. I thought about that with the work ‘Post trauma document Ashes to Ashes 2011 to 2015’. One thing you questioned, Won Jin, was the notion of recovery. I just watched a David Attenborough nature documentary about reforestation and this is the only thing to do. To reforest-rewild the Earth, after all this trauma.

AP: The notion of recovery also makes me think of what Iben Hendel Philipsen says in her interview with Peter Brandt, in the example of when Amnesty events focused on sexualized violence are held, victims are referred to as survivors. She disagrees with that because if we erase the victim, then we also erase the perpetrator out of the narrative. Her point being that as a survivor, you are put in an active position, implying that you acted to overcome. Whereas to be a victim is to affirm that you have been subjected to something, that you were passive and put in a set of conditions that you didn't want to be a part of. That's why it's so difficult to be a victim, the recognition of subjection. And it seems that Brandt doesn't see himself as a survivor. He also says that for him there is no full recovery from the trauma. That it's not something that you get over, but that it gives you a new set of conditions for living, talking to your point, Sophie, about ‘human’ nature as infrastructure.

AD: Brandt’s fight is very much about being recognized as a victim. ‘No safe place’ being published in Denmark, even before opening the book, the first thing I had to think was.. ‘what is a safe place if Denmark isn’t?’ That’s a very strong statement no, to say that there is nothing such as a safe place, even...

STL: For a white man. That's where the anger comes from.

_________________________________________________________________________________

Won Jin Choi is an independent curator living and working in Marseille. After having studied at School of Visual Arts in New York City she received an MFA from the Beaux arts de Marseille. In parallel with her individual curatorial projects, Choi, alongside artist Basile Ghosn, is the co-founder of the independent project space Belsunce Projects in Marseille. Her most recent projects include Hamish Pearch’s solo show Head Above Water, part of Manifesta 13 les parallèles du sud and the upcoming project Copie Machine in collaboration with Laura Morsch-Kihn and Antoine Lefevbre editions.

Sophie T. Lvoff is an artist and writer based in Marseille, with roots in New York and New Orleans. Her work is based on photographs and descriptions taking various formal manifestations including in-depth and critical research projects, writings, radio transmissions, and exhibitions. Lvoff holds degrees from New York University and Tulane University, and she attended the École du Magasin in Grenoble, and the post-diplôme of ENSBA Lyon. Her artwork has been displayed internationally, including at Prospect: 3 (the triennial of New Orleans), and the most recent iteration of the Lyon biennial. She has published her work in international magazines and art criticism websites, and is a contributor to *duuu radio. Lvoff is a professor at l'École supérieure d'art et design, St. Étienne.

Aurélien Potier is based in Marseille. He was an artist in residence at Triangle France - Astérides in 2019, where he worked towards the production of his first solo exhibition at Belsunce Projects (Marseille) in January, 2020. His practice explores vulnerability and intimacy. Text, often as the foundation of his work, is presented via performances, publications, sound and video works, and installations. In 2018 he created i apologize, a self-published and periodic zine. Since 2019, he has been working with Hugo Mir-Valette as one part of the duo AH!.

Aurélia Defrance studied Fine Arts in the ENSA, Dijon and Curatorial Studies in the Städelschule and the Goethe University, Frankfurt am Main. She has worked as a curatorial assistant in Portikus, Frankfurt; La Loge, Brussels and Triangle France, Marseille. She co-founded and programmed the Berlin based project space PMgalerie from 2009 to 2012 and has been invited as a guest curator in venues such as the Nassauischer Kunstverein, Wiesbaden; Galerie Parisa Kind, Frankfurt; Solalanotte, Frankfurt; Oslo 10, Basel and La Box, Bourges. She was part of the program CAPACETE 2016 in Rio de Janeiro and is currently based in Marseille where she works as an independent curator.

Peter Brandt studied at The Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts, Copenhagen and The Royal Institute of Art, Stockholm. His works are influenced by 1970s feminist body art, trauma theory, masculinity studies and art historical material. The wounded male body is Brandt’s most vital source, employed either through direct performative photographs and video works or in the making of hand-crafted works using a wide range of materials. In 2020 Brandt was awarded the 3-year grant from The Danish Arts Foundation and he has had residencies at Delfina Foundation, London, Cité Internationale des Arts, Paris, Circolo Scandinavo, Rome and The Danish Institute in Rome. Brandt’s latest solo shows include Monument to Violence at Memory of The Future, Paris, 2019 Post Trauma Documents at Västerås Art Museum, Sweden, 2016.