The Neon Colony Bar - a conversation with Samir Laghouati-Rashwan

Samir Laghouati-Rashwan (France, 1992) only recently graduated from the Marseille School of Fine Arts, but his practice is already self-assured and resolutely political. It blends multiple distinct approaches, including conceptual installations, publications drawing on images and archives, and films in which he appears or directs.

In the autumn, he created and presented on Instagram two videos titled The Neon Colony Bar, which he envisaged as an experience rather than as a completed work. Wielding irony with precision, he exposed, with kindness, the everyday racism that hides behind our naivety and unveiled the barely masked fantasies that we project onto bodies, plants and drinks in the (post)colonial era.

Flora Fettah Today we are revisiting the two episodes of The Neon Colony Bar, a few months after they were created and shown online. In order to understand the place that this project occupies in your practice, I wanted to revisit its origin and your research on the history of cocktails and the, so-called exotic, plants that they are composed of. Could you tell us where this interest came from and how it led you to this project?

Samir Laghouati-Rashwan The Neon Colony Bar was sparked by the appearance of English or Dutch alcohols, often gin, in African Films, like I Am Not a Witch by Rungano Nyoni. In this film, the image of gin recurs; people pour it in front of their front door to chase away bad spirits. I found this contrast interesting - you are in an African country, but to protect yourself you use a Dutch alcohol, which dates back to the colonies, which is the heritage of the colonies. So I began to wonder about the presence of these alcohols and research the history of gin. Pretty quickly, I fell on the history of gin and tonic. It was invented in India, we do not really know by who - there are lots of different stories. Some say that an English soldier created it in a bar, others say that it was created by Indians... We don’t really know, there isn’t an official story. But gin and tonic was the perfect cocktail for India as it’s a humid region that is very hot, with lots of mosquitoes. Gin is made from a thirst-quenching plant, which enables people to survive periods of great heat. But the most important part is the tonic – before it became known just by the brand Schweppes1– in which we find quinine that repels mosquitoes and keeps malaria at bay. At the same time, I was working in a bar in Arles that did cocktails. Gin and tonic was often on the menu, which intrigued me. So I began researching cocktails created in the colonies and, little by little, I realised that in 80% of cases there was cinchona, the plant from which we make quinine. It comes from Peru and was brought over to the Europe by Spanish colonial Jesuits in the seventeenth century. After being used to treat Louis XIV in 1649, it passed from being a sort of abstract medicine to being a recognised “true” medicine that had entered into Western and European science. What’s funny is that the plant is making a come-back today, as it is also the plant from which we make chloroquine. When I learnt that, I wanted to buy some seeds on the internet. That proved totally impossible as, with Covid, people have bought all the seeds to plant them at home and make their own treatments. It’s crazy.

From this research, I wanted to propose a performance for the exhibition Sur pierres brûlantes [On hot stones], organised by Triangle – Astérides at Friche de la Belle de Mai in the autumn of 2020. It was going to be a bar where I offered cocktails and told their stories, but this could not take place because of the health restrictions. So I had the idea of a series of videos, each one presenting a cocktail through two fictive characters, Benedict and Jane.

Samir Laghouati-Rashwan, The Neon Colony Bar, ep. 1, video 3'30'', 2020

FF Now we get to the heart of the matter! For this project, you chose to work with two actors, Madison Bycroft, who is also an artist, and Joel White. Why did you move from performance to directing others? How did you work?

SLR It was my first time directing people. It was important to work with people that I knew as I was imposing a burden on them: they are two white people and I made them pass for colonizers. Even if they were nice in the film, they represented nevertheless something really abhorrent. Madison and Joel are close friends and we often discuss these subjects together, which made things simpler. I made sure that they were okay to play this type of character, asked if they wanted to change certain things etc... In the end, the fact that I trust them allowed me to have fun with the text and in what I made them say.

We made it really quickly as it was the last week of the exhibition. I wrote everything the day before and we made the videos in one go. It is more of an experiment than a “finished product” that has totally come to fruition.

Samir Laghouati-Rashwan, The Neon Colony Bar, ep. 2, video 3'30'', 2020

FF The videos are very funny and imbued with irony. Is irony a frequent tool in your work? To what ends do you use it?

SLR My way of speaking and my relationship to the real are imbued with irony and sarcasm. It doesn’t work with everybody but it’s important for me, as it’s a way that I found for communicating ideas. It’s a way for me to be in the middle, to not have to choose between condemning people or awarding them with accolades.

I wanted to create representations that are plausible. We all have people around us who are like the characters in The Neon Colony Bar. Sometimes it’s difficult to give critical feedback because of the affect or because we do not have the intellectual background to be consciousness of what is problematic. I wanted to be inspired by these people, that I have also spent time with, who are present around us, who feel a certain nostalgia with regards to colonisation or for whom it is something very banal, or familiar. So for me, irony is a way of underlining this whilst trying to be subtle. So that some people can watch the videos and say, “Ah it’s true, my mate can be a bit like that too”. I don’t want it to be a caricature or offensive, as, without being patronising of course, the goal is to teach people, to share without creating a separation between “us” and “them” or simply between “us”.

In the end, the fact that I made the characters pretty realistic meant that the irony was not spotted by some of the audience. Certain people, who do not know me, felt really uneasy because they didn’t know what I was driving at, they asked themselves if I was not some sort of “white ally”. But that’s what I wanted, because there are moments which, when they happen to us, make us really uneasy as we don’t necessarily know how to react. When you are in a bar, when you come to drink, you are the most invisible person in the scene, whilst those who serve you are visible and run things, so we’re not going to put them in question – in that moment in any case, and above all not in public.

The decor is a clue, but it also creates a false association. It’s very colonial, with tropical plants, the map of the world, the African masks and even the clothes of the characters. But there is a bookshelf, on which you find James Baldwin, Franz Fanon and Hannah Arendt, which breaks this. If you watch well, you find small signs that allow you to say that this is all fake, this is fiction.

FF I feel like in these videos, with this project, you approach head-on colonisation and its heritage, especially cultural. Why is it important for you to confront yourself, and us, with the subject?

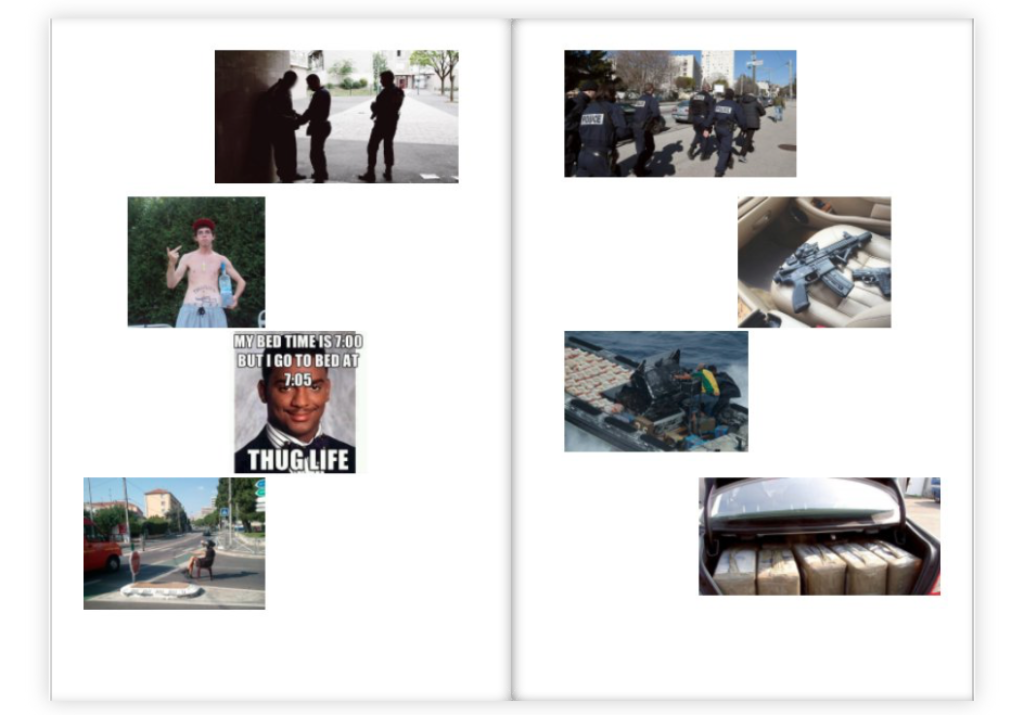

SLR Colonisation is part of nearly all of my research. When I started art school, I got to know myself. I thought I was someone, but I was quickly taken back to my state as a person of colour. So I began to research, for example, the clothing styles that came out of the colonial era or from slavery. The do-rag was originally a piece of cotton that slaves wore to protect themselves from the sun. Rubber boots were not like those we know today, but were pieces of rubber that were plaited together so that people would be able to walk in the swamps. The tracksuit rolled up on the right ankle reflects where the ball was attached to the ankles of slaves etc... They are things that are present in our daily life and that fashion has appropriated. That is also what is important for me, to hit upon a point where we really learn something, not just to criticise fashion or the art world or even colonisation, but to find what bears witness to this history and to politicise acts that we do not at all politicise – like rolling up your tracksuit or drinking gin and tonic. In the same way, I made a publication from some iconographic research that I did about the word “thug”. We usually think of “thug“ as coming from the world of English hip-hop, but in reality it comes from the word “thugees”, who were a brotherhood of assassins acting against the English colonial empire in India and whose speciality was to kill by strangulation. The publication starts from the definition of Tupac Shakur and displays a panoply of what represents thug from images that I collected on the internet. In French, thug is translated as “voyou” and the images turn around these clichés. So the question of colonisation has really been part of my work since the beginning, but through things that have not really been seen in that way. But actually for The Neon Colony Bar, the idea was to propose something that was very head-on and does not hide that it is examining these things.

Samir Laghouati-Rashwan, Thug Life, edition, 2016

FF The Neon Colony Bar is the first milestone in a larger artistic project, like a stage of research and experimentation, which you are currently working on. Can you talk to us about it?

SLR I started from cocktails, I discovered the plant, cinchona, and I began to research it. It’s in researching the ways in which colonial empires used plants that I fell upon the work of Pascal Blanchard, who wrote a number of books on colonisation, and on a documentary about the agricultural garden in Vincennes. I learnt that the garden had been a human zoo and then a hospital for soldiers arriving from the colonies during the First World War. It was very dense information that was not easy to absorb. I said to myself that I could not do something on this plant and this place without examining the history of the space. From here came the idea of making a film in Vincennes, at first in the form of a decolonial voyage in which a group of people meet to deconstruct their history. But, little by little, I realised that this was going to be complicated. First of all, I didn’t want to work with people without paying them and I had no budget. Then, I wanted to give voice back to the plants and not fall into, yet again, representing people of colour, which enters into a certain approach. Making the plants speak is also a way of protecting myself and the people close to me, to not overly expose us. I always try to sidestep, to look for gestures or insignificant forms that incarnate what is involved for us. It’s also a form of protection. I prefer to keep us safe whilst speaking about we live through other things. Also, there was this sentence by Samir Boumediene in his book The colonisation of knowledge: a history of medicinal plants from ‘The New World’ (1492-1750)2, in which he explains that we stole knowledge from plants and to which I wanted to respond by giving it back to them.

The human zoo was a large project: a designer thought about all the space, the pavilions, the shows, so that they would seem very traditional. They brought over theatre companies and people came, without really knowing what they were getting themselves into, because they were meant to be paid. But the conditions were in fact really bad and they were asked to replay their defeats - their deaths, their lost family, friends, loved ones. It was too hard, too sadistic. It was something that marked me and so I felt like I had to talk about it. Knowing this, I decided to give voice to two plants, like a grandchild with their grandparent, who tells their story, “We left there and we arrived here, we lived and here’s how we were treated etc.” The garden is full of stories and ghosts that I wanted to bring out. For example, there was “Little Capeline” who was from the Kanak tribe, in New Caledonia. She died when she was five years old and is still buried in the park. There were many deaths during the human zoo. Some countries wanted to take back the bodies, others left them.

FF To construct this project and its content, you surrounded yourself with a research group.

SLR Exactly. I often work on themes that are “in fashion” but I try to take my time to get down to work. I let the moment go by when these themes are trendy and then I work on them in depth in order to avoid the trap of superficiality. By really involving myself in the process, I try to not just offer a work of art that becomes inert in an institution, suffocated by all the patriarchal and colonial forces, but rather a gesture that remains alive. To do this, I constructed a research group that would contribute to the writing of the film and take part in a discussion each time I showed it. There is Samir Boumediene, who I already spoke about. Jessica Saxby, who is doing her PhD on the movement of seeds by boat during colonisation and who works with, and on, the Brazilian artist Maria Thereza Alves. Justine Soistier, a historian and anthropologist who works on the restitution of objects and archives. For me, it’s important that this project is not just the perspective of an artist on a subject, but really a bringing together of a lot of things, enriched by lots of people coming from different worlds. It’s in this way that the project will be as legitimate as possible and that it will last over time, without being superficial. It’s also important to keep it active after the film. There is a political engagement on the part of the institutions that accept to show the film accompanied by a discussion each time. That enables the members of the group to be remunerated and to continue to be together to share, not just to be used for their knowledge.

Samir Laghouati-Rashwan, ADN, video, 2017-2021 (still image)

FF And a last question, are you working on any other projects, apart from those we just discussed?

SLR Yes, a few weeks ago I released a sort of audio walk, which is made up of recordings of the interviews that I carried out for my final dissertation on wheeling, also known as wheelies or wheelstands. It’s called Tu Cross?, “You Ride?”3. There is also a publication in two parts. The first part is made up of an iconographic research that traverses from antiquity to today through the equestrian portrait, notably that of Napoleon by Jacques Louis David. I tried to foil Google’s algorithms by looking for representations that we don’t easily find, like those of a woman on horseback or on motorbikes or of non-Western men. The second part is a series of voices that respond to the question “What does wheeling evoke for you? What does it represent for you?”. Wheeling is a very controversial practice, it’s illegal, some people even go to prison for it. Others die during wheeling sessions or are killed by the police. It was important for me to not give my opinion on the subject, but instead offer open forms that can create a way to nuance what wheeling represents, without falling into fantasy or idealisation.

At the moment, I’m editing a film, called DNA, lost in 2017. In the film, I bring images from Hollywood films that depict Arab men as people who are violent, worthless, vicious and/or stupid face-to-face with the image of a clay pot being thrown on a wheel, referencing the myth of a potter who created and shaped the world in seven days. “To shape” is to repeat a gesture until we make a material take the form that we want. Cinema from America, and other Western countries, has shaped how a lot of people are represented and, with a political goal, forged numerous stereotypes: that of the Arab, the woman, the black, the Indian, the gay, the Asian etc. The title of this film – DNA – comes from a remark made by Jack Valenti, a lobbyist, advisor to the White House and president of the Motion Picture Association of America, who said in a speech, “Washington and Hollywood have the same DNA.”. Over the images, I read a text that I wrote. I really hesitated about who we should hear reading the text: a woman? A man? Me? But in the end, I read the text and I’m happy with the result.

Samir Laghouati-Rashwan, Tu Cross ?, podcast, 8'30'', 2021

Translation French - English: Bea Bottomley

Samir & Flora's bibliography

Each interview is punctuated by an exchange, a discussion where the author and the artist exchange ideas and references that are important to them. We were not able to reproduce all of them in the text, but this did not stop us from wanting to share them with you.

- Rungano Nyoni, I Am Not A Witch, 2017

- Franz Fanon, Peau noire, masques blancs, 1952

- Hannah Arendt, L’impérialisme, 1951

- James Baldwin, Chassés de la lumière : 1967 - 1971, 1972

- Samir Ramdani, Black Diamonds, 2014

- Pascal Blanchard, Zoo humains. De la Vénus hottentote aux reality shows, 2002

- Pascal Blanchard, Sexe, races & colonies. La domination des corps du XVe siècle à nos jours, 2018

- Samir Boumediene, La colonisation du savoir. Une histoire des plantes médicinales du ‘Nouveau Monde’ (1492 – 1750), 2016

- Jessica Saxby, A Botany of History: Plants, Seeds and Philosophies of Memory

- Abdessamad El Montassir, Résistance Naturelle, 2016

- Arne Saatkamp, Institut Méditerranéen de Biodiversité et d’Ecologie

- Ghita Skali, Ali Baba Express, 2018 – ongoing

- Sut Jhally, Real Bad Arabs: How Hollywood Vilifies a People, 2006